Hotspot JVM's Fast Locking based on displaced mark word

Introduction

This article describes the implementation of the fast locking algorithm that was introduced by Thin locks: featherweight synchronization for Java and is still available (as of June 2024) under the LM_LEGACY locking mode. The approach is already very well described in the aforementioned paper but this article aims to simplify the understanding of the approach described in the paper by going step by step through what happens when a thread locks on an object.

Note that the goal of the fast-locking algorithm is to minimize the overhead when a single thread tries to acquire the lock for an object. This is known as a non-contending situation. When the thin locks approach was introduced, reducing overhead in non-contending locks was particularly useful because some implementations of collections in the java standard library were written to be thread safe and to achieve that, they relied on synchronized methods. However, most of the time they were used in non-concurrent code, that still had to pay a big cost in terms of synchronization overhead.

How does it work ?

Acquire a lock

TLDR

When a thread T1 tries to acquire the lock of an object, it attemps to set a value in the object header that identifies our thread as the owner. This is done in an atomic operation usually known as compare-and-swap (CAS). If the CAS operation succeeds, our thread T1 has acquired the lock and it can continue running.

Detailed explanation

Let’s see a step by step process of a thread trying to acquire the lock for an object.

We can think of a java virtual machine running the following code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

public class MyClass {

public static void main(String[] args) {

getAccess();

}

public static void getAccess() {

var a = new Object();

synchronized(a) {

// do something

}

}

}

First, let’s look at two things that are relevant if we want to understand how our algorithm works:

- How Java objects are represented in the heap.

- How the virtual machine executes code.

Object representation in memory

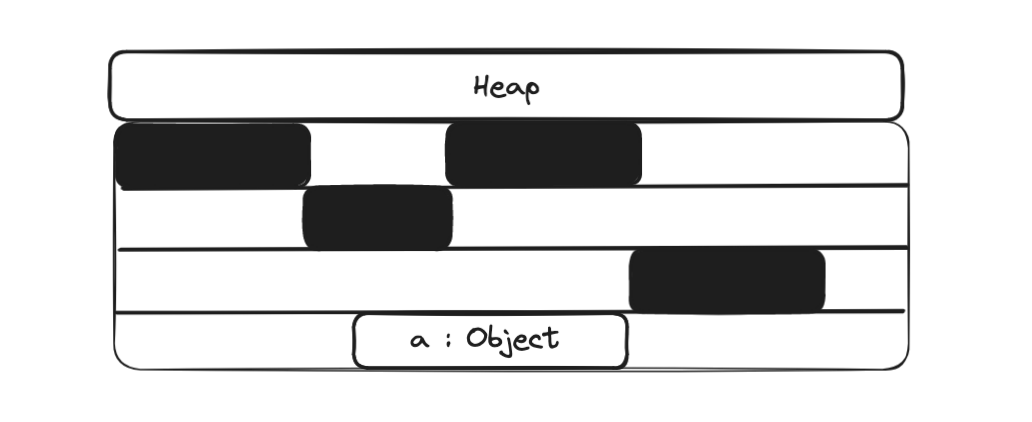

In the getAccess method, we first create a new object that needs to be allocated in the heap.

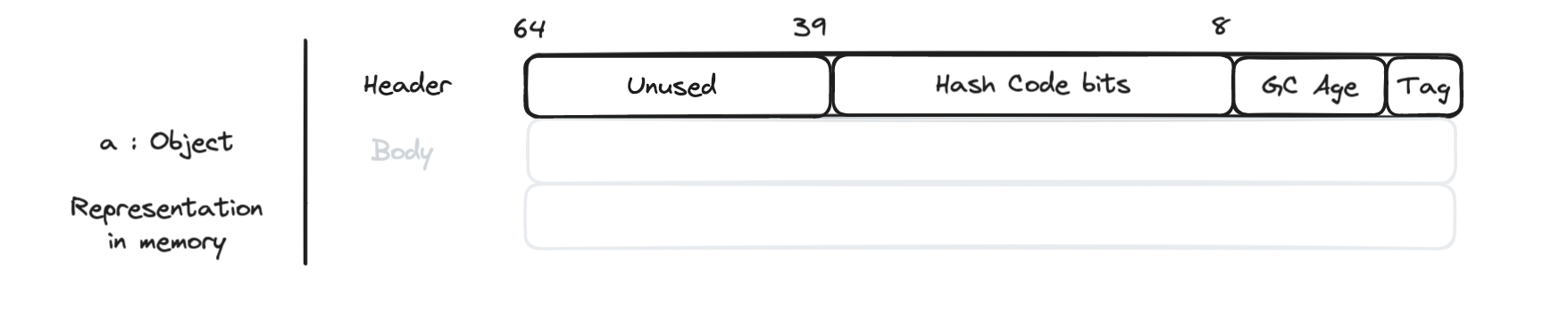

In memory, the object is represented by the header and the content. The thin locking algorithm relies on the object header to acquire and release the lock for an object.

JVM Virtual machine Stack

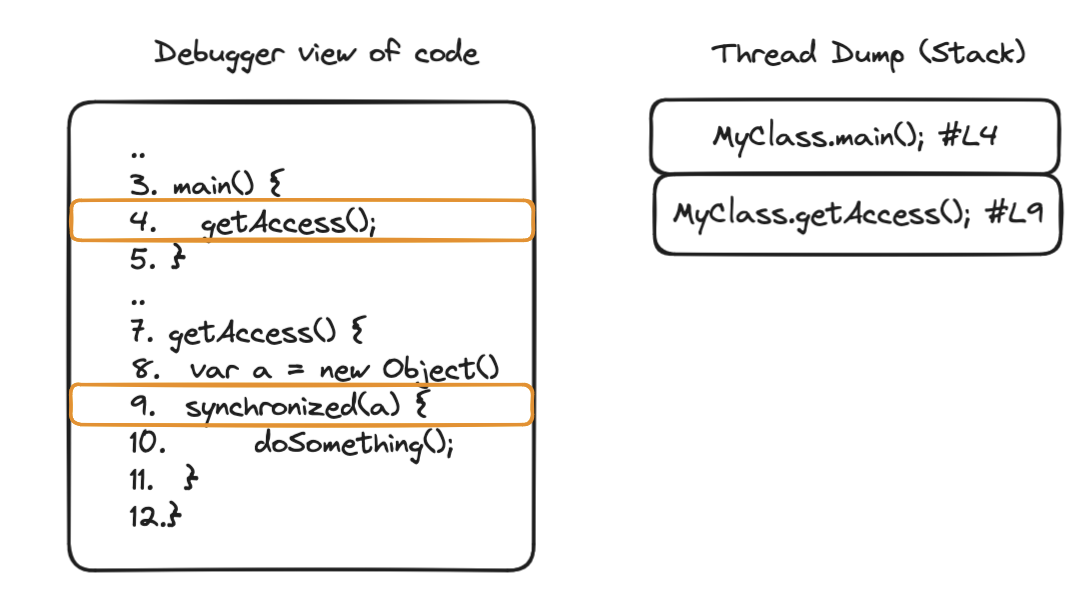

The Java virtual machine is stack based. Every thread will allocate a stack to keep track of the instructions to execute, local variables required and other metadata. Every call to another method will create a new frame on top of the stack. Let’s see a simplified version of a thread dump representing the stack for the code that we introduced at the beginning of this post:

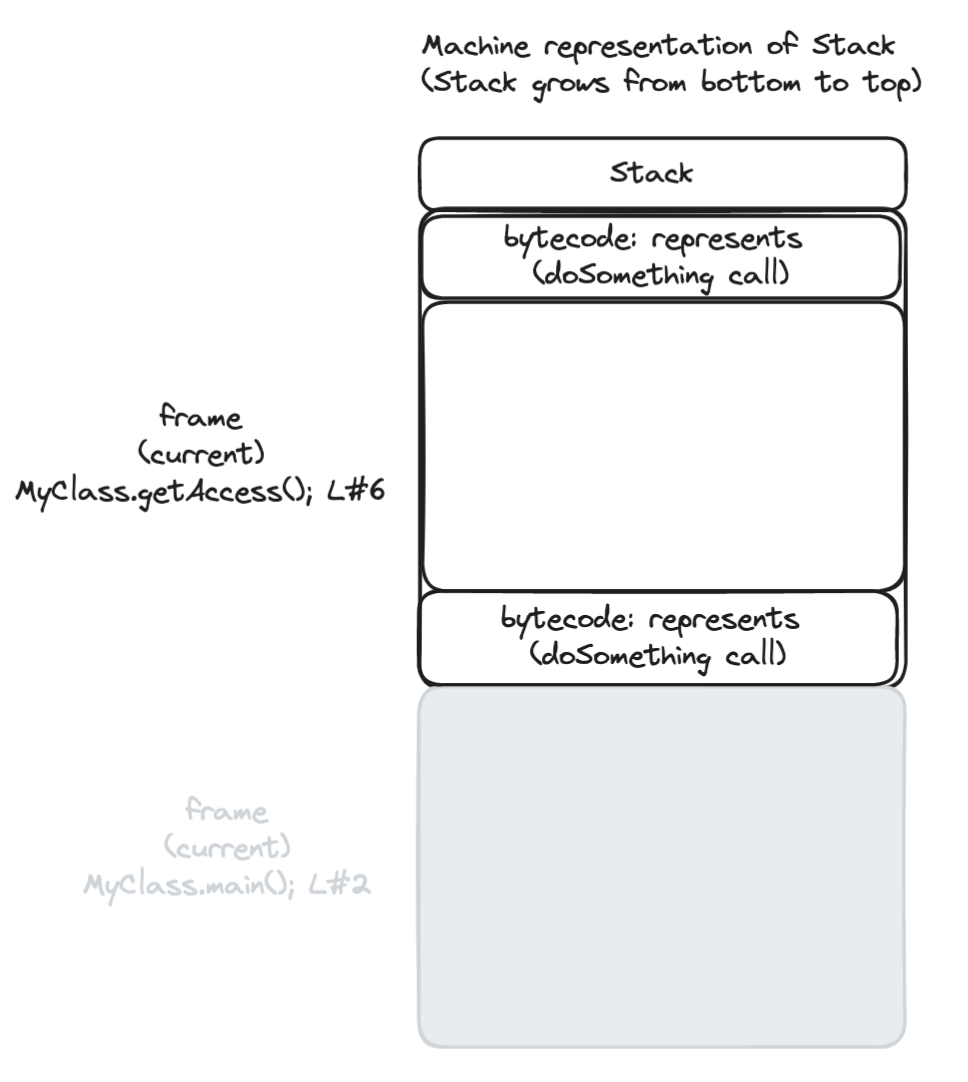

Now let’s have a closer look at how the JVM handles the stack. We will now look at the stack growing from the top to the bottom, because that’s the way that it happens when the JVM creates a new frame.

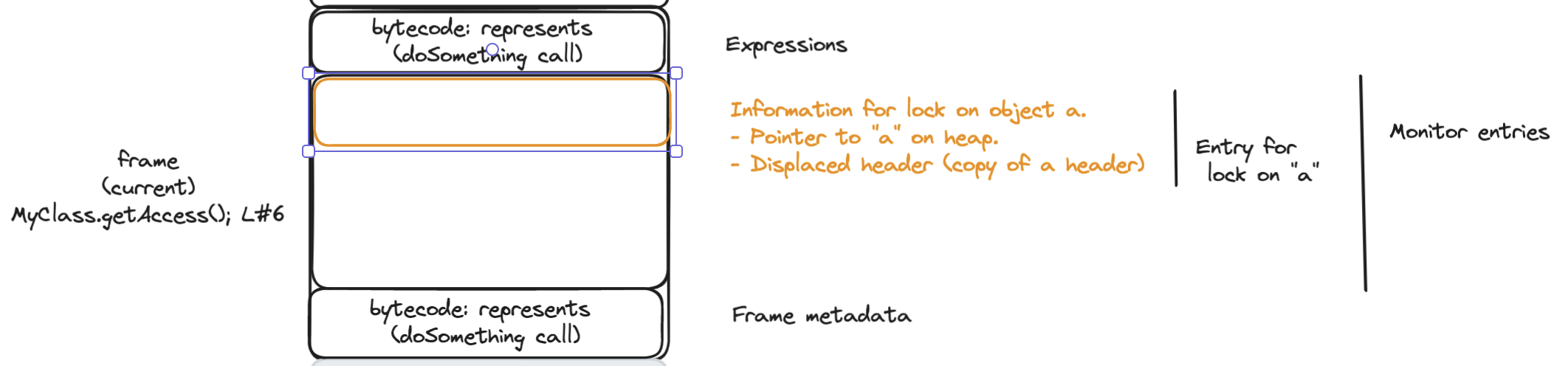

It is relevant to talk about the stack and its frames because the thin locking algorithm will use certain parts of the stack to store locking information.

Step by step - Acquiring a lock

Now that we’re aware of how objects are stored in memory and how the virtual machine executes instructions we can describe how thin locking works.

Let’s now see what happens when we reach a synchronized block:

- The thread tries to acquire the lock.

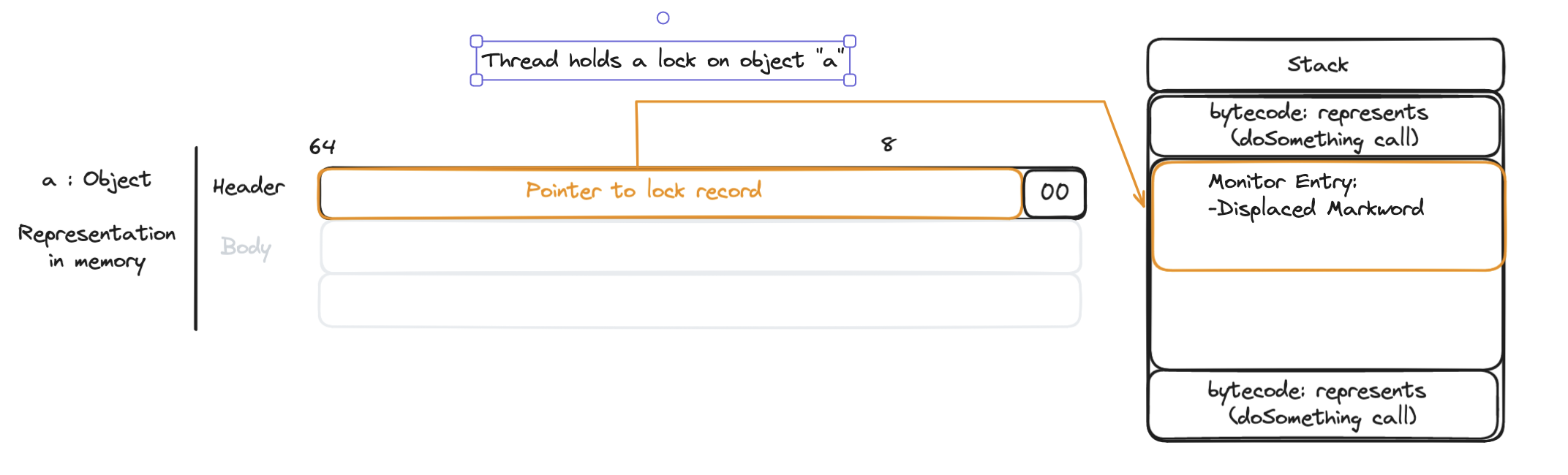

- The virtual machine, creates inside the stack frame a monitor entry, with a copy of the header (usually known as displaced mark word) and a pointer to the object that the thread is trying to acquire the lock for. This is known as the lock record.

Then, as described in OpenJDK - Synchronization and Object Locking:

-

The VM attempts to install a pointer to the lock record in the object’s header word via a compare-and-swap operation. See templateTable_aarch64.cpp

-

If it succeeds, the current thread afterwards owns the lock. Since lock records are always aligned at word boundaries, the last two bits of the header word are then 00 and identify the object as being locked.

Drawbacks of this approach

- Inefficiency: bits are left unused, so that they can be used in case of synchronization based on the object, but we only ever run synchronized on a few out of all the existing objects. Today this implementation is only used under the LM_LEGACY locking mode, a more memory efficient locking mode LM_LIGHTWEIGHT is actually the default approach. LM_LIGHTWEIGHT does a more efficient use of header bits by dropping the displaced markword and keeping track of the locks for a thread in a lock stack.

- Additional complexity in the code to read the markword, that needs to handle two cases: if there’s a lock it may need to read the displaced mark word but if it there’s no lock it can read it directly. (Note that this complexity is multiplied by the fact that multiple architectures provide different implementations to read the mark word)